Every so often I have a conversation that reminds me why I enjoy these long, unscripted explorations in the first place.

This week’s discussion was with Gibson Hanks, a 17-year-old who is deeply immersed in computers, programming, and AI. What made the conversation compelling was not just his technical fluency, but the way he thinks. Quietly. Methodically. With a strong bias toward first principles.

We started simply. When did you get your first computer? Did you take classes or teach yourself?

Like many of the most interesting builders I’ve met, Gibson is largely self-taught. He started ambitiously, jumping straight into C++, backed off when it became clear that frustration was outpacing progress, and later returned through more forgiving terrain like Python and JavaScript. Today, he works comfortably across web technologies, local servers, low-level signal processing, and locally run language models.

That arc felt familiar.

When I was seventeen, I was programming on a TRS-80, saving code to cassette tapes, completely isolated from the rest of the world. No internet. No cloud. No open-source ecosystem. Today, Gibson sits at the opposite extreme: unlimited access to papers, models, tools, and compute frameworks. Yet interestingly, he chooses constraint.

He runs models locally.

He avoids cloud dependencies.

He dislikes randomness.

He prefers deterministic systems he can fully understand.

That mindset became a recurring theme.

Representation Matters More Than Scale

One of the threads we kept returning to was representation.

Gibson is skeptical of large language models that grow primarily by adding parameters. He questions tokenization itself. Why words? Why subwords? Why not characters? Or signals? Or waveforms?

In his current project, he’s experimenting with speech synthesis not by generating audio end-to-end with neural networks, but by decomposing speech into its underlying components: resonant frequencies, filters, summed sine waves. He’s building vowels by hand. Listening. Adjusting. Learning.

There’s something refreshing about watching someone rediscover signal processing before defaulting to abstraction.

It echoed work I did decades ago in neural networks and cheminformatics, where representation was everything. Molecules were graphs. Biology was motion through conformational space. If you chose the wrong representation, no amount of modeling horsepower could save you.

Garbage in, garbage out is still undefeated.

Determinism vs Probability

Another tension surfaced repeatedly: deterministic thinking versus probabilistic thinking.

Gibson believes that, in principle, everything can be represented as a function. With enough data, enough structure, enough care, the future should be predictable. Markets. Speech. Behavior.

I pushed back gently.

History suggests otherwise. Noise matters. Hidden variables matter. Insider information matters. Schrödinger shows up whether we like it or not.

Yet what struck me was not disagreement, but curiosity. Gibson isn’t rejecting uncertainty. He just wants to reduce it wherever possible. He wants systems that behave the same way every time, so they can be tested, understood, and trusted.

That instinct shows up in his discomfort with AI systems that hallucinate, drift, or degrade over long contexts. He notices something many people miss: these systems fatigue. They decay. They need resets, summaries, breaks. They behave more like biological systems than most people admit.

Tools vs Understanding

We also talked about AI-assisted coding.

I described how modern coding agents now allow me to build in hours what once took weeks, how millions of lines of code have effectively collapsed into conversations. Gibson listened carefully, then admitted his hesitation.

He wants to know exactly what the system is doing.

He doesn’t like hidden layers he didn’t design.

He doesn’t trust code he didn’t reason through.

That tension is generational, but also philosophical. Do you optimize for velocity, or for understanding? Do you build components, or assemble outcomes?

The answer, of course, is not binary. But it was clear that Gibson’s joy currently comes from constructing the machinery itself. Engines before games. Tools before products. Foundations before scale.

That, too, felt familiar.

Education, Credentials, and Networks

At several points, the conversation drifted toward education. Degrees. Credentials. Whether they still matter.

My view remains nuanced. Formal education can provide exposure to orthogonal ideas, access to peers, and networks that compound over time. But curiosity-driven self-education, when paired with real projects, often produces deeper understanding faster.

Gibson is already doing the kind of work that once defined doctoral research: building tools in order to explore novel questions. The label matters less than the practice.

The real leverage, as always, comes from connecting that work to people. Universities, communities, and peer networks are still powerful testing grounds for ideas. Not because of the curriculum, but because of the collisions.

AI, Work, and What Comes Next

We ended, as many conversations do now, with AI and the future of work.

Gibson is realistic, perhaps even pessimistic. AI will eliminate more opportunities than it creates, at least in the short term. Knowledge work is already under pressure. Not everyone will adapt.

Yet within that disruption lies opportunity for those who build tools they themselves need. Local models. Smaller footprints. Faster, cheaper systems that do not depend on centralized platforms. Linux-like ideas applied to intelligence.

That theme resonated strongly with me.

The most durable technologies tend to emerge from builders who hate dependency, value autonomy, and design for their own use first.

Watching that instinct take shape in someone seventeen years old was quietly encouraging.

Not because he has answers.

But because he’s asking the right questions.

PostPod - Show and Tell

After the formal podcast wrapped, we shifted into a segment I like to call PostPod – Show and Tell. This is where conversations often get even more interesting, because instead of talking about ideas, we start looking directly at the work itself.

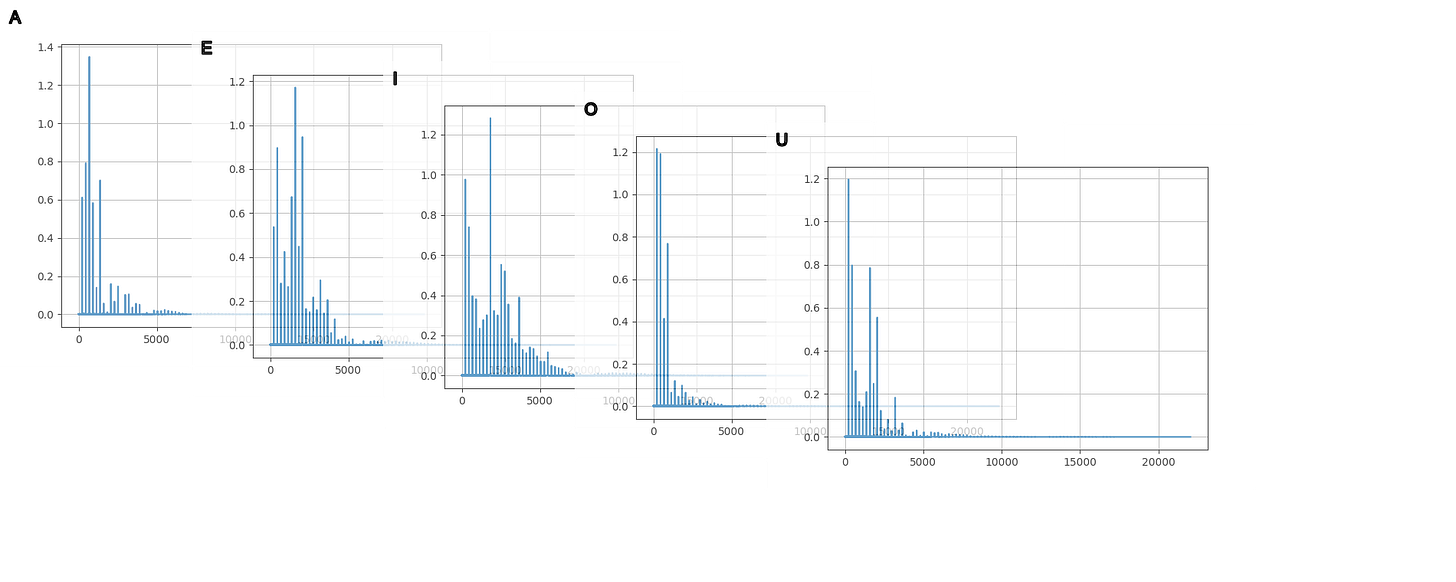

Gibson walked me through some of the tools he’s been building around frequency generation and sound synthesis. Using a collection of small utilities he wrote himself, he’s been experimenting with combining multiple sound waves over time to generate audio that resembles vowels and consonants. Rather than relying on large, opaque models, he’s exploring the fundamentals: how different waveforms interact, how resonant frequencies shape sound, and how surprisingly expressive simple building blocks can become when layered carefully.

At its core, what he’s doing echoes a beautiful idea that dates back centuries: the insight that complex signals can be constructed from simpler components. Long before modern AI, Fourier showed us that rich, continuous phenomena like sound can be represented as sums of waves. Watching Gibson rediscover and apply that idea firsthand was a great reminder that progress often comes not from adding complexity, but from understanding composition.

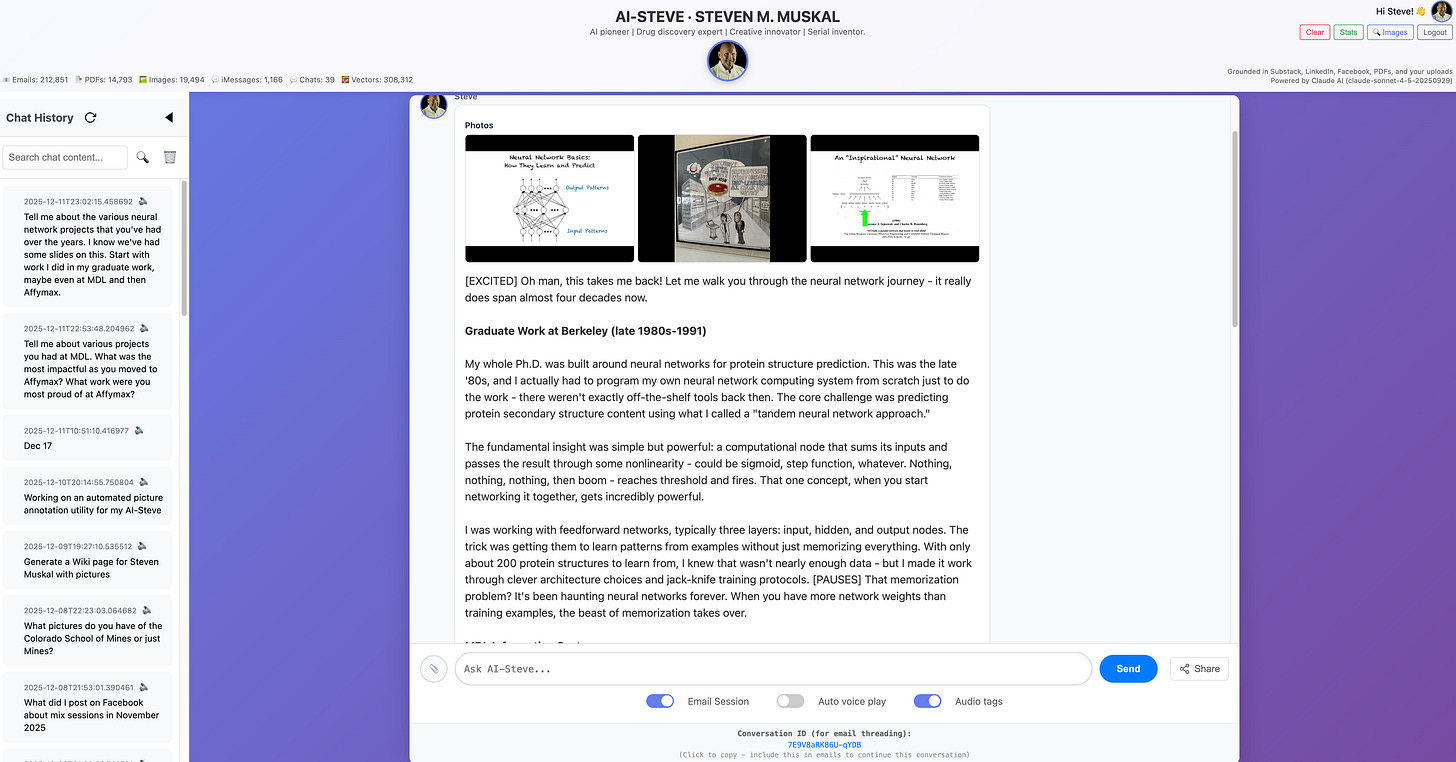

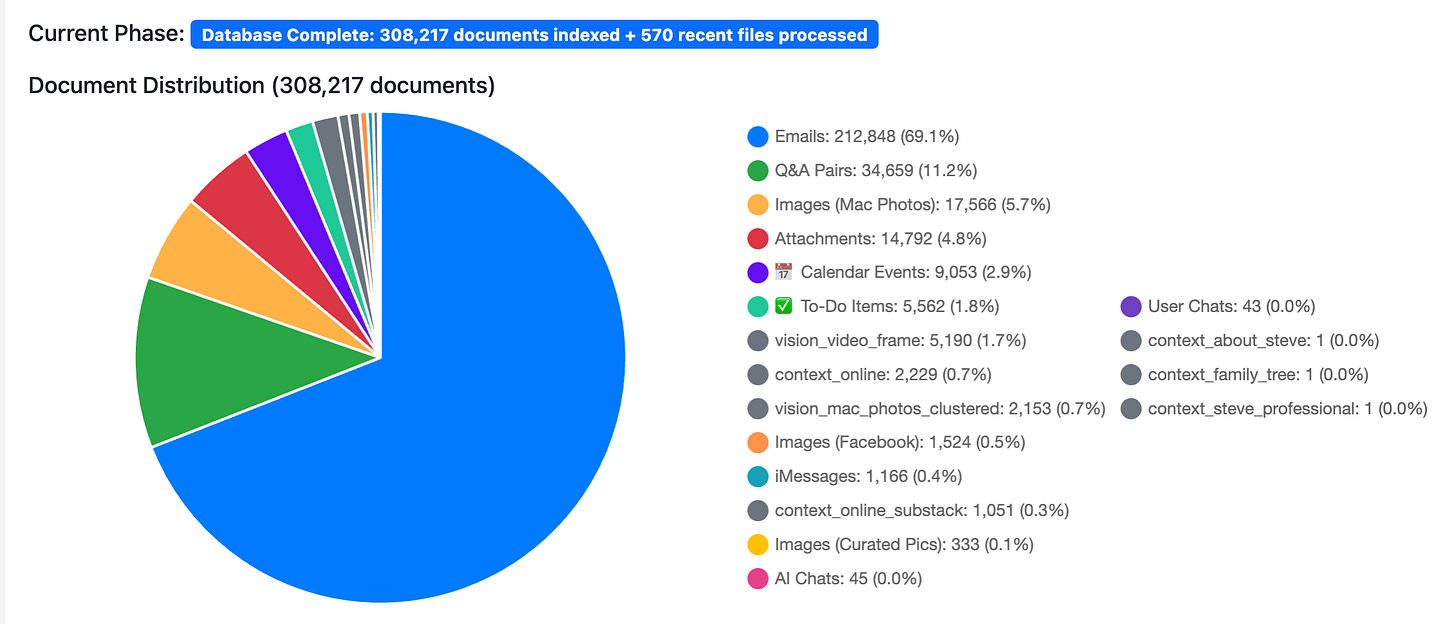

After Gibson’s demos, I returned the favor and showed Gibson my AI/Steve project, which builds on earlier work I did with AI/Dad. This new iteration uses a RAG (Retrieval-Augmentative-Generative) approach, but at a much broader scale. It continuously ingests multiple data sources related to me, updating daily, and uses that evolving corpus to ground responses.

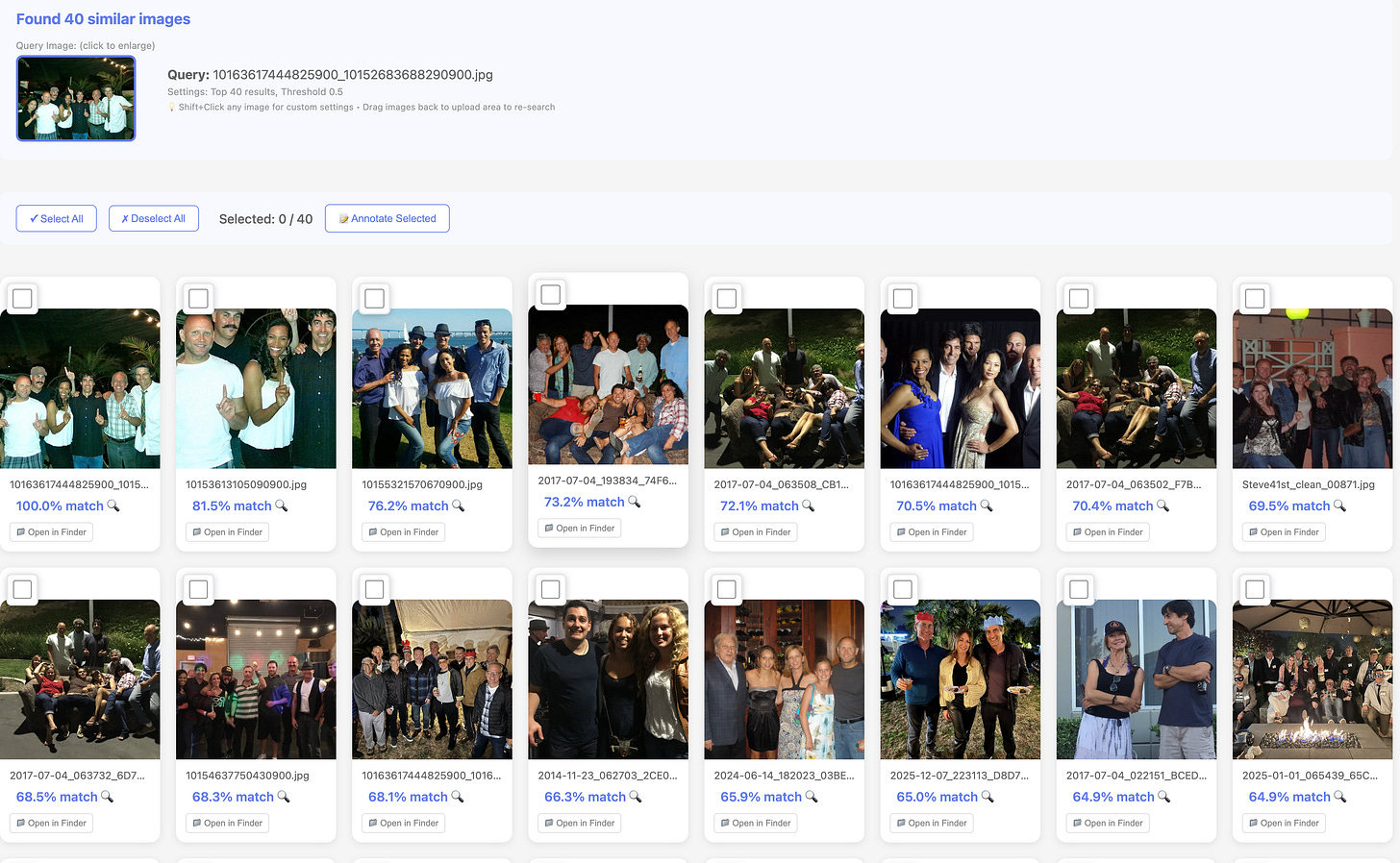

A big focus of our discussion was imagery - e.g. story telling. Photos and videos represent a massive portion of personal data, yet they’re often underutilized in AI systems because they’re difficult to organize and search meaningfully. As we discussed during the podcast, supervised learning lives or dies on annotated data. Without reliable labels, even the best models struggle.

To address this, I showed Gibson an ImageExplorer app. Like all the apps I have built recently e.g. Toast Apps, AI/Dad, AI/Steve, etc. I built the ImageExplorer system completely by speaking english language with Wispr flow into to different command line tools designed for “agentic coding” droid, claude code, codex, and occasionally gemini cli.). The ImageExplorer app allows me to search not just full images, but also sub-images within photos and videos. The system uses similarity and clustering to group related visuals and enables on-the-fly image searching, making it far easier to annotate content systematically rather than one image at a time. Once clusters or search hits are formed, annotation becomes fast, repeatable, and scalable, which dramatically improves the quality of downstream learning.

What struck me was how naturally our projects connected. Gibson is decomposing sound into its fundamental frequencies. I’m decomposing visual memory into searchable, annotatable components. Different domains, same underlying principle: representation matters. When you choose the right primitives, learning becomes tractable. When you don’t, scale alone won’t save you.

I’ve included a couple of screenshots below to give a sense of how the ImageExplorer interface works in practice. For me, PostPod – Show and Tell is always about this kind of exchange: two innovators, different stages, same curiosity, each walking away with new ideas to build and test.

Pretty cool stuff.

For clips, we had a fun session with some of my favorite musicians on my 59th birthday mix. So many to chose from, but here were a couple of my favorites. Tammy lead vocals with Maya harmonizing, Grant and Dom on Guitar, and Alan on Bass on Please Don’t Leave Me. The Second is Rick knocking it out of the park on Wicked Game. And the third was just a segment of the infamous Phil Collins fill I always wanted to try, and finally had a chance…